The Board Game Bonanza

Having spent a good portion of the first few weeks of this trying to design, redesign, and adjust the scope of a “bad drivers” then “bad customers” protest game, I felt at a loss with my actual game design abilities. Playtests with my brother and friends returned variations of “complicated” and “not really engaging”. When I changed the theme and gameplay to protest the troubles of driving via playing delivery drivers, it then “didn't really have enough of a protest feeling”. I set out for concepts that were, in my head, engaging and fast–paced, but ended up including many rules and actions in order to emulate the real-life things they were based on. In the end, there were too many rules and actions that made the flow of gameplay stop and start and slow down like a stalling car up a hill.

In the future, the delivery driver board game might yet get picked up again for non-protest purposes. However, through the course of this time studying how to think like a game designer, I was still able to exercise my way through theory and small design exercises and apply them to board game design outside of my first few stumbles. Eventually, I was able to wrap my head around the concepts that inform many game design choices, especially in board games.

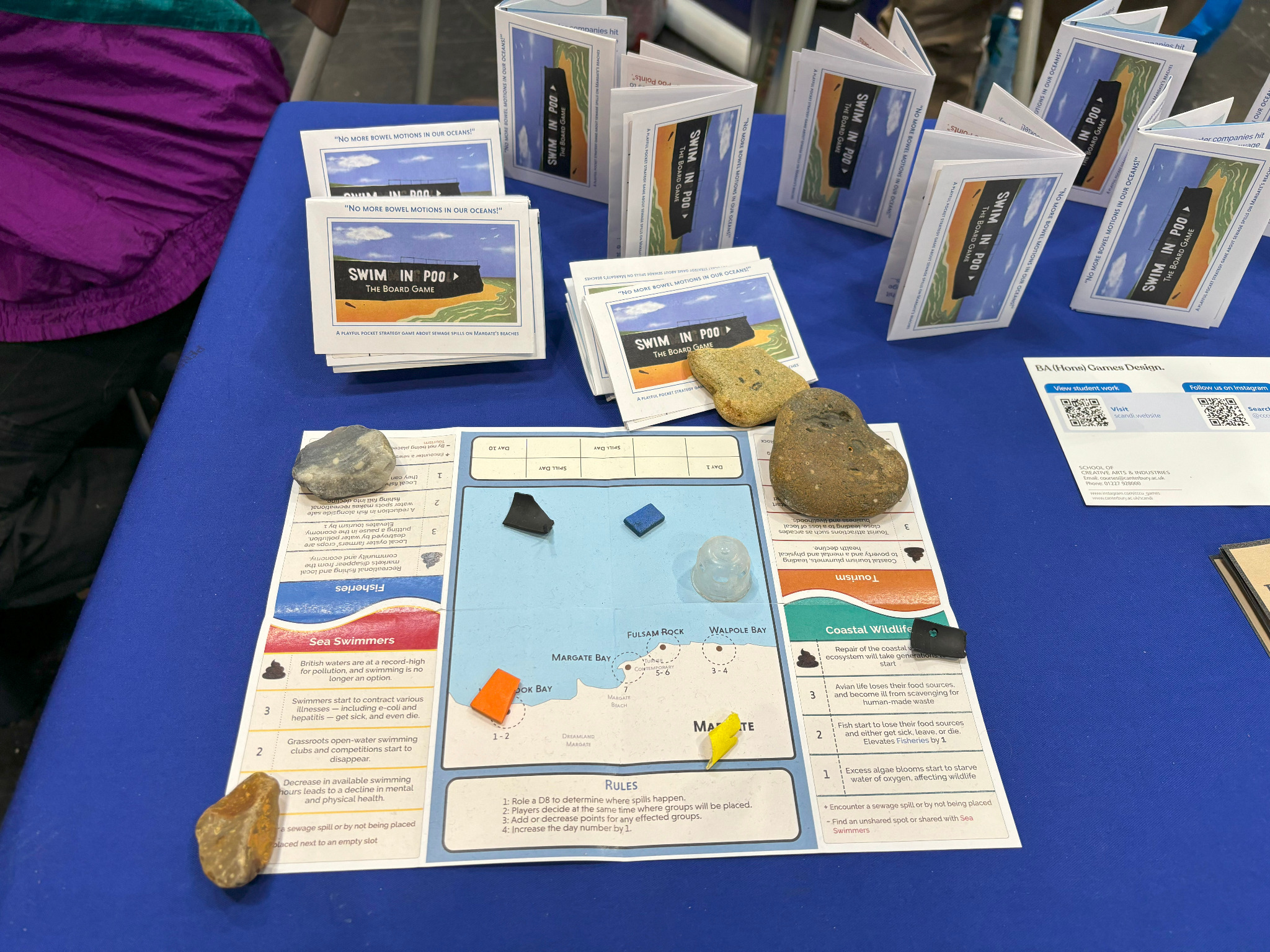

Having settled into working on the sewage dumping protest game, SWIM IN POO (working title), I was able to analyse, understand, and apply these concepts in practice. As the 2D artist on this, I had an additional focus on semiotics and graphic design, working on the booklet layout, formatting, and iconography to deliver a cohesive booklet-board reminiscent of coastal notice boards and old-timey seaside postcards. This went hand in hand with learning about rhetoric within games as a whole; specifically procedural rhetoric, and visual rhetoric. Visual rhetoric is especially important to me as a 2D artist, and one that I come across and unknowingly keep in mind during my work as an artist. This was a type of rhetoric that I could follow and understand most intuitively compared to procedural rhetoric – that, if a game wants to convey a certain message, emotion, or ideology, the visuals must also reflect that. Rhetoric exists as forms of persuasion, and so players must be persuaded that what they see makes sense within the context of the game, and conversely that the game is communicating what it is meant to by what it shows you on the screen (or in this case, on the board).

This element of reflection in games also leads into the concept of performative play. As the brief dictates that the game must be themed around an area of protest, it is natural that performative play becomes involved in this. Performative play applies to gameplay that directly and immediately influences the real-world through the game mechanics: as an example, play can occur in turning energy saving practices into a competition. In order to ‘win’ (or at least, not be the sole loser), people would have to actively cut back on their energy usage to have the smallest energy bill or other measurable metric among a pool of players.

As a point of comparison, persuasive technology works on a similar basis, but exists more in the context of consumerism, and employs coercive practices over a positive performative play. Ian Bogost, who first identified and differentiated performative play, has said that “recognition of the context is necessary, otherwise the performative fails.” In this case, the area of protest must be known and somewhat familiar to the player, or else there is little to no action/affect. For SWIM IN POO (working title), not everyone lives by the coast, and perhaps not everyone who lives by the coast experiences sewage dumping around their beaches. However, everyone is affected by pollution on some level, and people generally don’t like the idea of sewage being dumped into the sea, so the protest concept isn’t too niche for people not to support the idea of pushing back against sewage dumping.

[Current design]

SWIM IN POO (working title) has players collect pieces of plastic waste to use as their individual counters — unpaid litter picking through the medium of one board game! In providing only the board (made of cut–and–folded recycled paper) and prompting players to engage with the setting in a tangible way in order to play, we succeed in cleaning up the beaches bit by bit... assuming players will also bin said litter properly after playing.

*As a note at the time of writing this, a small reminder to bin the player counters should probably be included in the rules section.

Adding to said rhetoric is the use of unpredictable, real–life data that the player can reference for the board's map when they play. In the context of game design, Keith Burgun defines randomness as “information that enters the game state which is not supposed to ever be predictable.” For SWIM IN POO (working title), this randomness goes hand-in-hand with the element of performative play: players are required to set up their map at the start of the game , and this can be according to live sewage spill information from the provided website. This element of randomness is tied to real-life, as players wouldn’t know there is until they check - assuming the average player doesn’t somehow know when and where every spill will happen along the coast of Margate. Hidden information in this way pushes the game towards output randomness on Burgun’s proposed spectrum of randomness, but only enough to set the stage for players to engage with the game, and not to adversely affect their progression or completely limit possible player calculations. In order to assess whether the information horizon has been moderately placed to support this, there needs to be more playtesting where we can observe the balance of hidden information and the engagement with the core mechanic – it is likely that we would have to expand on it somehow while also keeping the possible amount of calculations at a hard limit, especially as this game is meant to be played quickly and easily.

Even after wrapping my head around several elements of game design so far, I still didn’t feel quite that confident in showcasing the game itself because it hadn’t been playtested a lot, yet. With the opportunity to work on and take this game to UK Games Expo (UKGE), I felt that this might be a big step without playtesting backing it, exacerbated by the fact that the prototypes we were handing out also had many minor but visible printing flaws, from the low resolution images, misaligned borders and text positioning, and awkward fold lines.

(As the 2D artist/designer for the game, I accept half responsibility for these flaws…)

… However, we were met with interest and success, most especially with regards to promoting our board game towards the education sector. Thanks to a talented friend who initiated the conversation, I was able to promote the game to a librarian who took an interest in the possibility of printing and stocking our game up at local libraries - at seasides in particular, but prospectively across the country. We briefly discussed how this might work; how the game could be adjusted for each location with references to locales, and visual elements specific to each library or location. Even if this particular avenue of library doesn’t end up coming to fruition right now, the designer and I coincidentally spoke about the same idea beforehand, with regards to editing the prototype to better reflect Margate, and make the game look more cohesive and reflective of our protest. Adjustments to the design would be straightforward enough without being costly or complicated, and production would be simple as there are no counters or pieces needed; plus the folding-and-cutting recycled paper option is both efficient and fitting for protesting pollution. The standard for output quality is lower because of this unique, travel- and eco-friendly format, so continuing to print the game like this wouldn’t be detrimental to the style or content of the game. Because of low production cost and the education sector angle, the game might be distributed for little to no price, possibly even as a website or similar online page for people to print out their own board. Alternatively, depending on whether there might be successful collaboration with anti-pollution organisations or local council initiatives, there might be an opportunity to gain more funding to print and distribute the game (currently, there is only one active group in Margate that we have attempted to make contact with). If development proceeds along this path, we can direct players towards donation points, charities, and crowdfunding for anti-pollution efforts as part of increasing awareness outside of the game, too.

To conclude, SWIM IN POO (working title) has been a great success and a promising board game to take even further, and being able to collaborate on it has been an educational experience. Going forward, I’m aiming to test how much performative play can be achieved with it, as well as practice the iterative design process more, putting the game through rounds of playtesting to see just how well it reflects the frameworks I’ve studied. I also aim to put what I’ve learned into practice on the benched delivery driver board game and revive that, too. Ideally, my work on one will continue to inform my work on the other, and having started to design two card games on the side, my time on this tabletop-based game designer crash course is shaping up to be longer than anticipated – a welcome and needed opportunity to better develop as a designer in the games industry.

Post a comment